.

AN

AUSTRALIAN

PILOT

237 (RHODESIA) SQUADRON

|

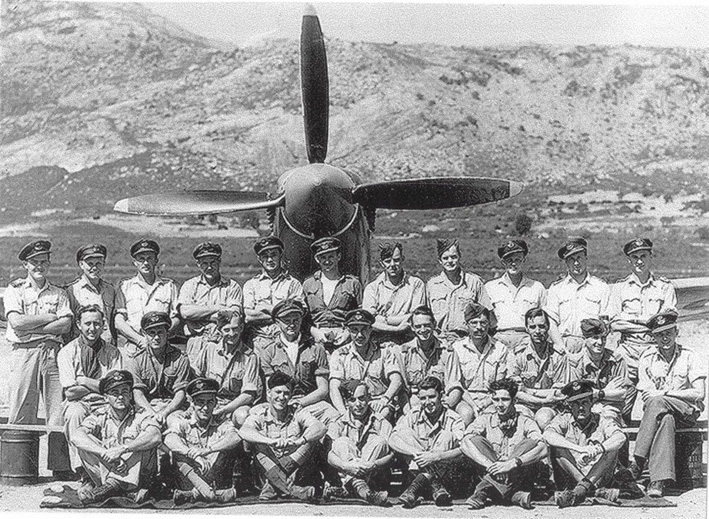

237 Squadron Pilots and Staff... photo taken at Calvi in August 1944 |

|

Back Row - Left to Right:

Pilots: Alan Douglas, Brian Wilson, Roy Gray, "Dinks" Moubray, "Polly" Payne, (Rhodesians),

"Red" McDermott, Adrian Burne (from England),

Harry Murdoch-Eaton, Pete Perterson, Jack Malloch, Keith Burrow, (Rhodesians).

|

|

Middle Row:

"Spy" Hughes - Intelligence Officer, (English), Boy Crooke - Pilot, Dave Howat - Adjudent, Lynn Hurst

OC A flight, John Walmisley, OC 237 Squadron, "Ippie" Ipsen - (from Denmark),

OC B Flight, Doc McCaw - Medical Officer, Don Currie, "Taffy" Williams - Aircraft Maintenance, (all from England), Peter Rainsford - Pilot

(Rhodesian)

|

|

Front Row:

Pilots: Bill Musgrave, Will Ford - (Rhodesians), Jack Hackett - (Australia), Bevil Mundy, Paul Pearson, Peter Sutton, Derek Hallas - (Rhodesians).

Not in Picture: Pilots Sam Aylward and Arthur Taylor - (Rhodesians).

|

|

Total Pilots: 25.

|

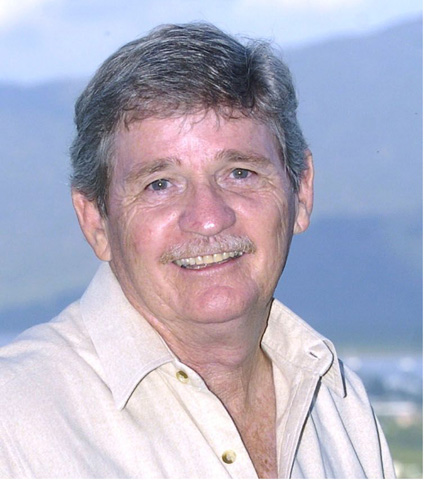

Jack Hackett, an Australian Air Force

Pilot, was posted to 237 Squadron in June 1944, shot down in the French Alps in

September 1944 and rescued by Italian Partisans. This is the story of how

he was traced and found alive and well in England some sixty years later, and

includes his account of the time he spent with the Italian Partisans and his

eventual escape through enemy lines to link up with American Forces in Southern

France.

Written by Bill Musgrave with input by

Jack Hackett – October 2004.

1.

Posting to

237 (Rhodesia) Squadron

237

Squadron formed part of No 251 Wing that was assembled in Corsica in April 1944

to provide air cover for the invasion of Southern France. Other squadrons

attached to the Wing were No 238 RAF Squadron and No 451 Australian Squadron,

all equipped with Mk VIII and Mk IX Spitfires. While at 73 OTU at

Abu Sueir In Egypt in early 1944, Jack Hackett requested to be posted to 451

RAAF Squadron, but instead was posted to 237 (Rhodesia) Squadron – arriving at

Serraggia on June 8th 1944. (In a similar situation Rodney

Simmonds requested a posting to 237 Squadron, but was turned down and ended up

on 238 RAF Squadron in May 1944, under the command of another Rhodesian, Archie

Wilson. I doubt that Rodney ever regretted this turn of events.)

While

awaiting the countdown to the invasion of Southern France, the Wing was based on

the East Coast of Corsica, together with U.S. Air force Medium Bomber and P47

Thunderbolt Fighter Squadrons. In April 1944 Corsica provided a very

strategic base from which to attack German Forces in Italy. The Allied

Forces were held up at Monte Cassino, a long way south of Rome, and the

situation at the Anzio Beach Head was getting a bit desperate. To bolster

their defences The German High Command decided to reinforce the Herman Goering

Division, and these troops were clobbered by the Allied Fighter Squadrons from

Corsica as they moved southwards along the roads through Tuscany. The

break through at Monte Cassino was achieved on May 20, the link up with Anzio

occurred a few days later, and Rome was captured on June 4th.

The whole German Army then withdrew northwards along the East Coast and through

Tuscany to a new defensive line in the Appenine Mountains to the north of

Florence. Once again the German Forces were subjected to continuous

strafing attacks from Corsican based aircraft and other squadrons based to the

south of the Allied Lines, and again the Germans suffered very heavy

losses of military hardware. During a bomber escort mission on one very

clear day it was possible to trace the whole Italian road network from burning

vehicles. These operations continued through June and part of July, and on

the 19th July 251 Wing were moved to an air fields near Calvi on the

West Coast of Corsica, in readiness for the planned invasion of Southern France.

Soon

after the move Ian Shand replaced John Walmisley as CO of 237 Squadron.

Sometime

after the move to Calvi, Jack took part on a mission led by the CO, escorting American

Medium Bombers to a target near Genoa. On the return trip Jack, conscious

of the need to conserve fuel, fell slightly behind the formation and the CO

instructed him to catch up. Jack opened the throttle and to his horror the

handle came out of the throttle housing. His plane accelerated sharply and

in no time he overtook the formation of bombers and fighters, and radioed the CO

to inform him that he had no control over his air speed. The CO radioed

back instructing Jack not to land at Calvi before the rest of the squadron, as

“he didn’t want the runway cluttered up with bits of aircraft”. When

Jack’s turn came to land he was very conscious of the timing of when to switch

off his engine so as to achieve the ideal combination of speed and angle of

glide to avoid a ditch at the approach to the runway, and not to overshoot at

the far end.

Unbeknown

to him an audience had gathered on the runway expecting to witness a crash.

But Jack accomplished a perfect landing, missing the ditch with a smooth

touchdown, controlling the direction with rudder and brakes, and finally braking

to a standstill well within the limits of the runway. Lying in bed that

night and thinking about the incident he suddenly came to the conclusion that

he’d been a bit of a fool, realising that he could have shut the engine on and

off at will simply by using the power on/off switch and allowing the rotating

propeller to re-start the engine.

On

another occasion Jack remembers flying on a bomber escort mission to a target

near Florence, with all aircraft fitted with 45 gallon long range drop tanks.

Jack took note of the time of take-off and after 45 minutes decided to switch

over to his main tank. He switched off the feed from his drop tank and then

switched over to his main tank – wrong sequence! Within a matter

of seconds the engine stopped and the aircraft plunged into a downward glide

falling away from the main formation. Jack grabbed hold the auxiliary fuel

pump lever and commenced a vigorous pumping action. For what seemed ages

nothing happened and Jack began thinking of a forced landing, and then

suddenly the engine started with a mighty roar and Jack was back in business.

2.

The Invasion of Southern France

The

invasion, code named Operation Dragoon, was set for 15th August 1944,

with the main landings to take place in the area of the Beach Resort Areas of St

Tropez, St Raphael and Frejus. The Invasion was originally intended to

coincide with the main Invasion in Normandy in June 1944, using American Troops

from Italy which would become surplus to requirements after the link-up of

forces battling at Monte Cassino and Anzio. The original plan would have

allowed for a two-pronged attack through France from the west and south, which

would have facilitated its capture. The delay in this link-up postponed

the Invasion of Southern France by some two months, and no doubt contributed to

the increased severity of the fighting in Normandy.

The

softening-up process in the south of France started a couple of weeks before the

invasion, comprising attacks on coastal installations by American and Free

French Medium Bombers from Corsica and Sardinia, while Corsica based

Fighters scoured the road and rail networks in Southern France attacking

vehicles and trains, and other military targets. In one instance 237

Squadron was delegated to attacking radar installations along the coast, and on

one of these flights Jack suffered the infuriating experience of one of his

cannons jamming and slewing the aircraft off the line of fire.

Meanwhile additional Spitfire Squadrons were transferred to Corsica from Italy,

and dispersed on the three airfields at Calvi, creating one of the largest

concentration of Spitfires ever assembled, made up of eleven RAF Squadrons, one

Australian Squadron and two or three U.S. Air Force Squadrons, in total about

260 Spitfires.

The

troops for the invasion were gathered from the American 7th Army

Forces in Italy, and assembled in the Naples area, comprising seven Armoured and

Infantry Divisions, and an Airborne Glider Division. A massive fleet of

800 Ships were provided and the whole force embarked and set sail on August 13.

They passed through the straits separating Sardinia and Corsica and arrived

offshore of the invasion beachheads in the early hours of the 15th

August. Huge Naval Guns and Bombers pounded the coast while Landing Craft

loaded with troops and weapons headed for the beaches. Fighter Aircraft

from Corsica provided continuous air cover, and continued inland attacks of

military targets. The large force of Glider Borne Troops, in 332 Gliders, landed

a short distance inland, and by the next day a link up with one of the Beachhead

Divisions was established. The invasion was in effect a

“walkover”, and the main objective was achieved in two weeks. This was

due largely to the low morale and inexperience of the German Troops, the

depletion of their forces to reinforce the armies in Normandy, and the

unexpected aggressive response by the French Resistance Forces.

Hitler

described August 15th as “the worst day of my life”.

He had just survived an assassination attempt, German Forces in Russia were in

full retreat, the Warsaw Uprising was getting out of control, the Armies in

Normandy were facing defeat, and the remaining German Forces faced complete

encirclement in France. The fact that Germany was able to recoup and

launch counter offensives and continue the war for another nine months was a

remarkable achievement.

3.

A Short Spell

in Southern France

In

the days following the invasion, beachhead patrols continued and some bomber

escort missions were carried out. Some 10 days after the Invasion, the

Fighter Squadrons from Corsica started to move to bases in Southern France.

No 251 Wing were relocated on August 27th to Cuers Airfield in the

district of Aix-en-Provence, a few miles north of Toulon. This was a

famous airship base in pre-war years, and included a huge airship hangar, taken

over by a US Squadron of light aircraft, which could take off and get airborne

inside the hangar and come flying out through the open hangar doors. Soon

after arrival at Cuers the CO informed Jack that he had recommended him for a

Commission.

Due

to the virtual cessation of fighting in the southern France, aerial activity was

reduced to cover for some bomber missions, standing patrols and weather recess.

However, early in September Intelligence reported signs of a German thrust over

the mountain passes from Italy, and 251 Wing were instructed to investigate.

The first flight was carried out 9th September covering an area of

the Alps between Turin in Italy and Briancon in France, but there was no

evidence of any significant military build-up, and very few vehicles were seen

on the roads. On 21st September a flight of six aircraft were

dispatched on a fresh mission, led by Ian Shand. Jack was a member of this

flight, flying as No 2 to Dinks Moubray. They flew towards the southern

most point of the Alps, about 20 miles to the north of Monaco and spotted

vehicles moving along the Tende Valley in the vicinity of the French-Italian

Border. They dived to attack, flying at a low level along the length of the

valley and destroyed some 12 vehicles. As Jack pulled-up behind Dinks

Moubray he noticed his engine was vibrating and slowing down. He

sensed something was seriously wrong and radioed the C.O., who told him his

glycol cooling system had probably been hit and damaged and that the only option

for him was to bale out – the severe mountainous terrain precluding any

possibility of a “belly” landing. At the same time he instructed Jack

to climb and get over the crest of the mountain and bale out in the adjoining

valley, to avoid falling into the hands of the Germans they’d been strafing.

Jack managed to stagger over the crest at reduced speed and was seen to bale

out. Dinks Moubray followed him down, noticed a large tear in his chute,

but saw him land safely. On October 11th the squadron was

officially informed that Jack was safe in the hands of Italian Partisans.

That was the last the squadron heard of him.

4.

The Search for Jack Hackett

In

January 2003 we were put in contact with an Air France Regional Airline Pilot by

the name of Alexandre Durastanti who lives in Bastia, Corsica, and devotes

nearly all his spare time to research and correlation of aerial activities over

Corsica during World War II. He has accumulated a phenomenal amount

of detail in every aspect of military aviation, and is only too willing to share

this information with other interested parties and respond to any queries on

related topics. Corsica was home to the 12th U.S. Air Force

from 1943 to 1945, made up of Medium Bomber and Fighter Groups spread over

twenty air bases, and comprising mainly B-25 Mitchells, B-26 Marauders and P-47

Thunderbolts. Alex has devoted most of his time to researching the

operations of the US Air Force Groups, including visits to meet ex-American

Aircrew in the U.S. More recently he has extended his coverage

to RAF & Commonwealth Squadrons, initially establishing contact with the 451

RAAF Squadron Association in Australia.

I

was put in contact with a certain John Poate, a Pilot who flew with 451 Squadron

in Corsica and was shot down while strafing a German airfield in Italy, and

taken Prisoner of War. John Poate undertook to try and track-down Jack

Hackett and contacted several air force related institutions, but without any

success. The problem was that we did not know Jack’s service number, and

later we learnt that ‘Jack’ was a nickname – his given name was John

Albert Hackett. If John Poate had known this he probably would have found

him.

At

this point Alex took up the challenge. Alex’s approach was to

contact all Australians with the name of Hackett. He obtained

163 names and addresses from Telephone Directories via the Internet, and on 9th

May he started posting a standard letter and photo to each address, describing

the background to Jack’s involvement with 237 Squadron, and ending with the

comment ‘Hoping this message in the bottle will find someone with an

answer’. Within a short while he received some replies with

encouraging information, but no positive identification. Then on 14th

June he received the following e-mail message from a Michael Hackett living in

Queensland, Australia, a relation who was aware of the name ‘Jack’. :

Dear

Mr Durastanti,

I

read your letter with great interest. A real blast from the past it

seems.

I

am reasonably sure that the person in the photo is my Uncle Jack who served in

the air force in the Second World War and was indeed shot down and lived with

partisans in Italy, as I understand until the end of the war. My father

Jim was also in the Australian Air force but was in New Guinea. Jack

lives in England with his son Geoff Hackett in Staffordshire. You can

contact him directly through Geoff. Good luck,

MICHAEL HACKETT.

So

contrary to our assumptions that Jack, if still alive, would be in Australia, we

now learn that he is living in Staffordshire, a mere 1½ hours drive from Milton

Keynes. This news triggered an immediate follow-up. On Sunday 4th

July we motored up to Lichfield in Staffordshire to meet Jack at his son

Geoff’s home, and his son Bryan travelled down from Yorkshire to join us.

Meeting Jack again after a lapse of sixty years was an stimulating sensation.

We settled down in the lounge and started to reminisce on our time together on

237 Squadron. Bryan set-up a sound recorder and we enticed Jack to give an

account of the sequence of events he went through from the time he baled out.

These are described in the next chapters. In the days preceding this

get-together Bryan had been browsing the Internet and a search under the name John

Albert Hackett revealed details of an Italian Historian by the name of

Sergio Costagli, specialising in the research and publication of historical

events, which occurred in the Maritime Alps of NW Italy during World War II.

Details included a considerable amount of documentary and photographic evidence

of Jack’s activities after he was shot down. In Jack’s account of the

sequence of events he frequently mentioned the name of Eugenio Meinardi, a

medical student who could speak basic English and helped him a great deal after

he was shot down. Bryan e-mailed this information to Sergio who replied

that he knew Dr Meinardi, now retired, and that they lived close to each other

in the city of Cuneo.

At

Alex Duratstanti’s request we then arranged for him to meet Jack. Alex

flew over from France and stayed a couple of days with us. On Thursday 29th

July Brian collected his father and brought him down to Milton Keynes to meet

Alex and spend the day with us. After months of effort and perseverance in

searching for Jack the eventual meeting was emotional for Alex – with a “Dr

Livingstone I presume” ring to it. Alex has a good understanding of

English and an exploratory chat followed.

5.

Baling-Out

– Rescue By Partisans - Hide-Outs - Shoot-Outs and Back Over the Alps on Foot

to Allied Lines

After

being hit while strafing, which damaged the glycol cooling system, Jack managed

to entice the Spitfire over the southern ridge of the Tende Valley at reduced

speed, and levelled out to avoid stalling. He then set about the tortuous

ritual of baling out from a Spitfire. He pulled back the perspex canopy,

undid his straps, opened the side door and knelt-up in a bent posture within the

confines of the cockpit, his feet on the seat and leaning over sideways towards

the open side of the cockpit, and simultaneously controlling the angle and

direction of the aircraft with his right hand on the joy-stick. He then

took quick stock of the situation and dived out head first, very conscious of

the closeness of the tail-plane to his body. Unbeknown to Jack his

parachute caught the sharp edges of a cartridge clamp on the right side of the

cockpit as he dived out, tearing a slit in the silk chute. Everything

seemed to be happening at once, and Jack, contrary to standard practice,

immediately pulled the ripcord. The chute opened successfully with a sharp

wrench on Jack’s body as it unfurled, but due to the torn slit he descended

faster than normal and he hit the ground rather hard, but without causing any

serious injury.

On

landing Jack proceeded to hide his parachute in accordance with standard

practice but he was unable to dig a hole, so he gathered it up and covered it

with branches and foliage. He then sat down to rest and reflect, and

unpacked his ‘emergency rations’ package. He opened the slab of

chocolate, which exposed a packet of unhealthy looking dust that blew-away in

the wind, concluding that it must have been a left over from World War I.

He then unpacked a small compass, thinking he’d have to set a southerly course

to get out of the mountains, but found it to be useless. He then took out the

package of 10 cigarettes and proceeded to smoke them on the spot. He then

set-off and using the sun as a guide he headed in what he thought was a

southerly direction, which took him parallel to the valley below where he

noticed German vehicles. After a while he heard some voices ahead, and hid

behind a large boulder to see what was going on. Within a very short

distance he saw a canteen with 20 to 30 German Troops drinking beer and joking

amongst themselves, and concluded that he’d better get out of there pretty

quick.

In

an endeavour to get into a safer area he decided to head-up the side of the

mountain and try and cross the valley heading into France, but time after time

he encountered precipices and sheer cliff faces. He persisted for several

hours and by dusk was getting a bit desperate, and also worried about

encountering mine fields. As darkness was beginning to set-in he came

across a clearing and saw a shed with lights shining from it. After some time an

old man emerged, and shortly after walked back inside which happened several

times.

Jack

weighed up the situation, thinking ‘here was an old man living on

his own up in the mountains, whose life span preceded Mussolini and the German

occupation, who more than likely would be sympathetic, and at worst not in

favour of reporting him to the Germans. Also, he would be a better bet than

trying to find his own way home through the mountains, bye-passing German

positions and minefields unassisted’. So Jack approached and knocked

on the door of the shed and held his breath.. The old man let him in and

Jack pointed to the wings on his battle dress blouse and said “Inglese

Pilota”. The old man sat him at a table and brought him several

helpings of soup and some bread and water. When he had finished the old

man took him outside to a small shed in the yard and indicated that he should

sleep there. They went inside and the shed was crammed with sacks of

potatoes, and as Jack settled down the old man went outside and locked the door.

Jack believed that this was not a bad omen in the sense of being reported to the

Germans, and feeling “cheesed off” with the day’s events, settled down

amongst the bags of potatoes and slept.

At

daybreak the following morning Jack was woken by the rattling of keys in the

lock and the opening of the door. In walked a young medical student by the

name of Eugenio Meinardi who could speak basic English, followed by a

middle-aged man who was second in command of the local Partisan Group, and a

third man whom Jack assumed was the person in the village that the old man

contacted to lead him to the Partisan’s hideout. Eugenio greeted Jack in

English and then acted as an interpreter while the 2/IC of the Partisan Group

questioned Jack in detail to verify his claim to being an English Pilot. Then

Eugene asked Jack if he knew of the tune ‘Deep Purple’ and whether he

could remember the words, and Jack was able to recite three lines, including ‘where

the deep purple falls over sleepy garden walls’. This finally

convinced the group that Jack was genuine and everyone relaxed. They asked him

if he had any money, and he had a wad of French Francs, which he gave to them.

They gave this to the third man who disappeared. They continued chatting amongst

themselves, and it was clear that all now believed him. Then after a

couple of hours, in walks the third man with about six bottles of cognac and

cigarettes. Between the four of them they downed two or three bottles of

cognac, after which the 2/IC put the remaining bottles aside, probably for his

CO. They then sat around chatting and smoking, and eventually fell asleep

until late afternoon. Eugenio then informed Jack that they were going to take

him to the Partisan Base. They gave Jack a coat to cover his uniform and

set off down to the German Occupied village of Tende, where they walked through

a narrow back street in single file, with the third man leading, followed by

Jack.

A

German approached them from the opposite direction, walked past the third man

and came up against Jack, and in typical gentlemanly fashion they offered each

other the right of way hopping from side to side in turn. Eventually the German

got a bit impatient and muttered something in anger, so Jack let him pass.

He continued past Eugenio and the 2/IC and continued on his way. Soon

after the third man left them to go home. The remaining trio continued through

the village and started to head-up the side of the mountain for a couple of

hours in darkening light until they came across a rough track where they halted

and flashed a signal with a torch. A flashlight signal then appeared from some

distance ahead indicating that all was clear and that they could proceed.

They followed the rough track in a downward curve and came across a long hut in

which there was the CO and 30 to 40 Partisans. They went inside and Jack

was introduced to the CO, who then had a lengthy discussion with the 2/IC, and

all seemed fine. Eugene then informed Jack that they were to sleep there

that night. Jack, the CO, the 2/IC and Eugene settled down in a small

compartment, had another slug of cognac, smoked and fell asleep. The

remainder, including two rough looking Russian Soldiers who had been rescued by

the Partisans, slept in the main area of the hut.

Jack

estimates they spent two to three months in this location high up in the

mountains. They were well aware that there was a strong force of Germans

down in the valley, and the Germans in turn were aware that there were Partisans

up in the mountains, but with evidence pointing to an early ending of the war

they did not relish a brawl. Similarly the Partisans refrained from moving

down into the valley to harass the Germans. To gain a better idea of when

the war may end the CO and 2/IC questioned Jack at length on the progress of the

Allied Armies through Normandy and beyond, and the situation on the Russian and

Italian Fronts. During the time they were living in this hut several things

happened. One day they ventured out through the snow and moved up the

valley, and at a certain point a dozen German Soldiers appeared in front of

them, with neither side giving the impression that they were looking for a

fight. They stood and stared at each other with neither side “requesting

the next waltz”, and eventually the Germans turned and walked away. The

Partisans suspected that they would collect reinforcements and return, so they

decided to vacate the area. They gathered up their baggage of blankets,

guns and ammunition and moved out through very thick snow. They walked for

about two hours, with Jack having difficulty in keeping up.

Eventually

they stopped besides a mound of snow and started to dig, revealing a door, which

they walked through to expose a concrete bunker, with icicles stretching from

ceiling to floor, and freezing cold. They decided to sleep there, and

proceeded to burn some wood to warm the place but this only created suffocating

smoke. They eventually settled down body against body for warmth, covered with

blankets and slept through the night.

The

following day they moved out of the bunker and headed further up the Mountain,

arriving at a clearing where there was another long building, similar to the one

they left the day before. They occupied this building, laid out their

bedding and stayed there for about one week. Nothing happened until one

morning about 6 am the door opened and a Senior German Officer walked in

together with a Junior Officer, probably on an inspection tour. They immediately

realised they were in amongst 30 to 40 Partisans and were hesitant about what to

do. The Senior Officer mumbled something and then slowly turned around and

walked out through the door followed by the Junior Officer, and headed across

the clearing towards the trees. The Partisans, many of whom had been

roused from their sleep, were then fully alert and questioned what they should

do. “We’re going to get them” shouted one, and grabbing their vast

array of weapons they streaked out through the door and chased after them.

Jack then heard a lot of shooting from among the trees and eventually the

Partisans returned with the main items of the Germans’ clothing and weapons.

So Jack presumed the two Germans had been killed, probably on the grounds that

there was no other alternative. Following this they immediately

“upped stumps” and returned all the way back to their original hideout in

the long hut where they had originally met the CO.

They

resumed daily guard duties, and by this time there was snow everywhere and as

the days passed Jack took the opportunity to try some skiing. During this

time people occasionally came up from Tende to request medical attention for a

member of the family. Eugenio attended to these cases, going down to the

village to see the person, and prescribing some treatment. Eugenio,

who by this time had become Jack’s minder, asked if he would like to accompany

him on one of these trips, telling him that he might find it a long walk, but

he’d get a good meal. So one evening they both walked down to the

patient’s house in Tende where Eugenio examined and prescribed treatment for

an old man, after which his wife went to a lot of trouble in preparing a

delicious meal. They then had to struggle back up the mountain in deep

snow on full stomachs, eventually arriving back before dawn.

Jack

had gathered the impression that the population of Tende were aware of the

Partisan band in the mountains and had developed a certain liaison with their

presence.

During

this time Jack was aware of an elderly man who had come up from the direction of

Tende to meet the CO, and learnt that he knew a route over the mountains to the

American Lines. Jack asked Eugenio to enquire whether he could join him

the next time he made this trip, and the reply came back "You certainly can

but we will have to wait for the snow to harden to facilitate walking through

the thick snow and to avoid leaving any footprints”. Eugenio added that the

two Russians would also be going.

This

became a frustrating wait for Jack, who was out every morning to check

conditions - the hardening of the snow required a few days of calm weather

followed by a sharp frost to freeze the snow. Then finally after a couple

of weeks, towards the end of November 1944, Eugenio informed him that the Guide

would be attempting another crossing the next day. The Guide duly

arrived and after bidding farewells to Eugenio, the CO and 2/IC, the group set

off in the early evening – the guide, Jack and the two Russians. They

climbed up the mountain and eventually reached the upper ridge where the Guide

told them to keep below the ridge to avoid providing a silhouette against the

sky for anyone watching. They walked through complete darkness all night.

At

one point the Guide stopped and positioned everyone close together one behind

the other, and proceeded to edge his way through a minefield. Poking

around with a stick as he moved, he suddenly stopped and made everyone move to

the right, pointing out a mine immediately in front of them. In this way

he guided them past three or four mines and finally out through the far side of

the minefield. As dawn broke they came across an open clearing with a lot

of heaped haystacks, and it became evident to Jack that the timing of their

passage through the minefield and arrival at this point was the reason for

starting their trek early the previous evening. The Guide made them

borough into the haystacks where they relaxed and slept all day. Jack,

without thinking lit a cigarette and had a smoke, and suddenly in a flash

realised how stupid he was, thinking he could have set the whole of North Italy

alight.

Come

darkness on that second night they set off again and continued through the

mountains, again negotiating another minefield. As dawn broke the

following day Jack noticed that they were now moving down towards the valley.

The Guide signalled that they could relax, and pointed to an empty packet of

Camel Cigarettes, a sure sign that there were Americans in the vicinity.

They walked on for another couple of miles and came across a clearing where they

could see American Army trucks. In total they had travelled about 8 miles.

Jack, wearing Italian Army clothing, approached a gum-chewing GI who was leaning

against a truck having a smoke, and asked him where he could find their

Commanding Officer. The GI did not question him and merely indicated a row of

houses, pointing out the one at the end. At this point Jack bid

farewell to the two Russians and expressed his deep gratitude to the Guide,

shook his hand and bade him farewell. The Guide and the two Russians

continued into the base, probably to hand over the Russians at an appropriate

reception. Jack then went up to the end house and knocked on the door, and

an officer appeared and invited him to come in. A second Officer appeared

and they proceeded to put him through the usual interrogation session – full

name, rank, squadron details, base, details of mission, where shot down, etc.

The Senior Office then said “OK, we’ll give you a meal and you can rest

here, and this evening we’ll take you down to Nice”. This was early

December 1944.

They

provided Jack with some American clothes, shoes and shaving kit and drove down

in a Jeep to a Hotel in Nice in the early evening. Jack was given a room

and was invited to join a dinner party with the Americans after he’d settled

in and had a bath. At 7.00 pm they called for Jack and went down to

the Dining Room and joined a party of about ten Americans, including some women.

A proper meal was served and Jack chose a steak dish. He took one bite and

was unable to swallow anything, so he excused himself and went back to his room.

One of the Americans followed him and asked what was wrong. Jack replied

that he was feeling sick, so the American told him to have a good sleep and in

the morning he’d take him to Doctor. In the morning they took him to an

Army Doctor who diagnosed Yellow Jaundice, brought about by a deficiency in his

diet during the past few months. He was taken to hospital immediately

where they put him on a special diet, with daily blood counts. He remained there

for about two weeks, and during this time a British Liaison Officer visited him,

and following the usual interrogation session Jack asked the Officer if he could

arrange for him to get some money to purchase some writing material and stamps

so that he could inform his family that he was ok. The Officer replied in

the negative, claiming that there was nothing he could do under the

circumstances, but did promise to look into the matter. The happy climax

was that three Americans gave him $10 each, so Jack was able to pass on the good

news to his family. After two weeks Jack was discharged from hospital and

transferred to a Transit Camp in Marseilles, and then flown to Naples on 5

January 1945, where he ended up in the well-known 56 PTC – Personnel Transit

Camp.

He

was interviewed again by a British Army Officer and asked what he wanted to do

– return to Australia, a posting to England, or what? During his transit

through England, prior to boarding a ship to Egypt, he had spent some time in

Lancashire where, in Jack’s words ‘he had met a lass and become semi

engaged’, so he chose to be posted to England.

This

episode in Naples begs the question of why Jack was not offered the option of

returning to 237 Squadron? At this time the squadron was based in Italy,

and as far as I can remember we were not even informed of him being in Naples

– if we were, a couple of us would certainly have flown to Naples to greet

him. Ian Smith went through a similar experience after he was shot down in

June 1944 – aircraft glycol cooling system damaged by ground fire while

strafing in the Po Valley, tried to make it to the Gulf Of Genoa to bale out

over the sea, but burning engine forced him to bale out north of Genova, joined

a band of Partisans who after several months helped him to escape along a route

extending from a village north of Genoa, passing through the Alps south of Tende,

and meeting up with the Americans at a point a few miles further south from

where Jack came through. They had walked for 23 days, covering a distance

of about 90 miles. This was late November 1944, a mere few days before

Jack came through the lines.

Ian

Smith’s escape has been well documented. Of interest is the mention of

two regulations applicable to ‘evaders’ returning to Allied Lines: i)

if missing behind enemy lines for more than three months one is entitled to a

posting back home. ii) upon return to the Allied side, one is to be

returned to the unit under whom he was operating at the time he went missing.

Ian had a strong desire to go to England, and while at Marseilles he had tried

to get on a direct flight to England but this was overruled on account of ii),

and he was sent to Naples. The Interviewing Officer in Naples told him that he

could be transferred to Cairo immediately, from where arrangements could be made

to get him home. Ian replied that he had a strong wish to go to England as

he had several relatives there and it was in fact his second home. The

Officer nodded his head and said ‘If that’s what you want, that’s fine’.

Ian Shand happened to be in Naples, on squadron business, and he called to see

Ian. He tried to persuade him to return to 237, but to no avail. This was

the end of the first week of December 1944, about the time that Jack was

spending the night at a hotel in Nice.

The

fact that Jack was also sent to Naples from Marseilles implies that this was

done in accordance with regulation ii) above, as was the case with Ian Smith,

but according to Jack there was never any mention of him returning to 237

Squadron. Instead, Jack in accordance with his request, was flown to

England on 15 January 1945, where he was posted as an Instructor to No 57 OTU,

flying Spitfires once again. He received some good news at this point on

hearing that he had been granted a commission on September 10 1944, so that from

the time he was shot down his pay had accumulated at a higher rate. He was

promoted to the rank of Flying Officer on March 10 1945

In

closing, Jack wishes to express his gratitude to the various people who helped

him in this venture, commencing with the old man in the mountains who sheltered

him for the first night and put him in contact with the partisans, to the CO and

2/IC of the partisan band who accepted him within their midst and shielded him

from the Germans, to his new friend Eugenio who helped him continuously and gave

him companionship and guidance, and finally to the old man who guided him over

treacherous mountain terrain to freedom.

Photographs courtesy of Mr Alexandre Durastanti

Sincere thanks

to Bill Musgrave for the story and for agreeing to its distribution to ORAFs.

Thanks to Tony Smith and

Selwyn Johnston for their help with the Australian Flag. Distributed to ORAFs in

January 2006

The Jack Hackett Story

The Jack Hackett Story

![]()

![]()